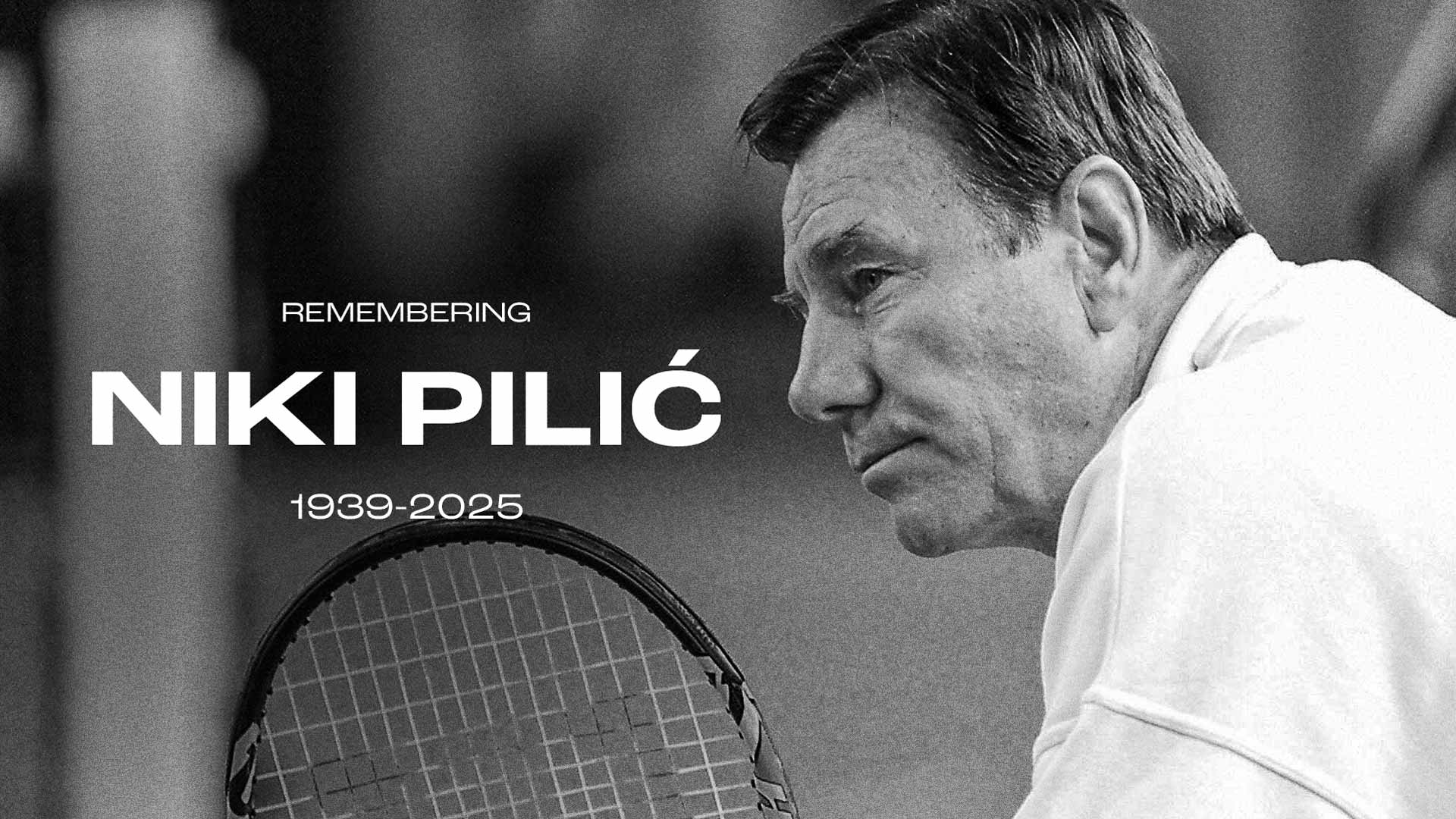

A lefty’s legacy echoes across tennis eras

Nikola Pilic’s thunderous serve and unyielding principles propelled him from Yugoslav courts to the heart of tennis’s defining rebellions, leaving a blueprint for champions and the sport’s soul.

Sparks ignite on divided courts

In the humid haze of 1952, a 13-year-old Pilic first swung a racket at Split’s Firule club, the post-war air thick with rebuilding dreams amid his shipbuilding studies. Four years later, he claimed five national singles titles and seven in doubles for Yugoslavia, his big serve booming down-the-line to set up inside-out forehands that left opponents scrambling on slower clay. The lefty’s game blended brute force with tactical guile, his underspin backhands skidding low on grass, building a resilience that carried him into the pro ranks where every match tested the era’s fractured loyalties. By 1962, partnering Boro Jovanovic, he reached Wimbledon’s doubles final, the Centre Court crowd buzzing as they traded volleys in the fading light. Five years on, in 1967, Pilic surged to the singles semifinals, dismantling Roy Emerson with precise crosscourt exchanges that turned defensive lobs into punishing overheads. His tall frame loomed at net, poaching with a predator’s instinct, the grass’s quick bounce amplifying his serve’s awkward kick to the right-handers’ backhands.“Niki was a very talented player, with his serve and forehand being great weapons,” Stan Smith reflected. “He was also a good thinker and he came close to winning some big tournaments.”

Clay storms and boycott thunder

May 1973 thrust Pilic into turmoil when the Yugoslav Tennis Federation slapped a nine-month suspension for skipping a Davis Cup tie against New Zealand in Zagreb, his pro commitments clashing with obligatory duty. Fresh from a Roland Garros final loss to Ilie Nastase—where red clay dusted his whites and the Parisian throng chanted through grueling baseline duels—the International Tennis Federation upheld the ban, later trimming it to one month that shadowed the Italian and German Opens plus Wimbledon’s dawn. Pilic’s mind raced with defiance, his training sessions in Munich a blur of forehand loops against the void, each stroke a pushback against the encroaching silence. Outside London’s High Court in June, he stood resolute with Drysdale, Arthur Ashe, and Jack Kramer, the summer warmth fueling debates that echoed the sport’s growing pains. Compromises dissolved in the heat; 81 male players, the ATP’s fledgling ranks formed just months prior in September 1972, voted to boycott The Championships, their walkout a thunderclap on empty grass courts. This stand for autonomy—players dictating their calendars amid the grind of circuits—solidified the player-led organization, evolving into the ATP Tour by 1990 through mergers with directors.“Obviously he was the trigger point for the boycott at Wimbledon. We felt as a fledgling ATP that players should be able to play where they want, when they want,” Smith shared with ATPTour.com. “We backed him not because of who he was, but because he was a member of our association, who was not being allowed to play for what we felt was not a good reason.”

Mentoring minds amid national triumphs

Retirement channeled Pilic’s fire into guidance, his Oberschleißheim academy near Munich a disciplined haven where tactical drills cut through the crisp Bavarian air. There, he captained Germany to Davis Cup glory in 1988, 1989, and 1993, orchestrating matchups like Becker’s booming serves against clay grinders, transitioning to Stich’s net rushes on faster surfaces. For Croatia in 2005 and Serbia in 2010, his steady hand navigated indoor hard-court tensions, Ivanisevic’s lefty spins mirroring his own to disrupt with inside-in forehands and down-the-line backhand passes. He molded raw talents—Becker’s baseline endurance, Stich’s all-court poise, Ivanisevic’s emotional volatility—instilling a psychological core that turned pressure into precision, huddles alive with whispers on reading spins and varying paces. In 1999, under Jelena Gencic’s auspices, a 12-year-old Novak Djokovic arrived for three months, absorbing lessons in mental fortitude: countering topspin with underspin blocks on clay, then unleashing flat strikes on grass to build the unyielding focus of a 24-time Grand Slam champion.“We are deeply saddened by the passing of Niki Pilic, a true pioneer of our sport. His contributions across many roles left a lasting impact on players, fans and the game itself, and hold particular significance in the history of the ATP,” ATP Chairman Andrea Gaudenzi stated. “He will be greatly missed. On behalf of the ATP, we extend our heartfelt condolences to his family and loved ones.”