Building champions layer by layer with Frederic Fontang

As the ATP Tour winds through its grueling autumn stretch, coach Frederic Fontang layers technical precision with mental steel, turning raw potential into resilient contenders who chase titles under arena lights.

In the quiet intensity of practice sessions and the electric hum of tournament arenas, Frederic Fontang crafts careers like a meticulous builder, refining every facet of a player’s game from the baseline’s grind to the mind’s quiet battles. His approach unfolds with deliberate care, addressing the snap of a serve, the slide into a forehand, and the resolve that holds firm through five-set marathons. Players emerge from his guidance not just sharper, but unbreakable, channeling the roar of crowds into inside-out winners that shift momentum in a single point.

Foundations forged in early partnerships

Fontang’s coaching odyssey began after he retired from the tour at No. 59 in 1999, opening an academy in Pau where he first met a 12-year-old Jeremy Chardy, a local prodigy full of promise but raw in execution. Over 11 years, he guided the young Frenchman through the ranks, culminating in a Top 30 peak by blending tactical drills on clay with mental conditioning to weather the isolation of junior events. This partnership laid the groundwork for Fontang’s method, emphasizing gradual builds where slice backhands evolve into aggressive one–two combinations that dominate crosscourt rallies.

Shifting to the women’s circuit, he spent two years with Caroline Garcia, smoothing her transition from junior success to the WTA’s relentless pace. He fine-tuned her returns against towering serves, instilling the poise needed for tiebreaks where doubt can unravel a lead. Garcia’s growth highlighted his ability to anticipate pressure, adapting inside-in forehands for hard-court speed while fostering the confidence to extend rallies under fading daylight.

“The coach is an architect, a guardian of the process,” Fontang told ATPTour.com. “We are in the business of competition, of results. The players want to win. They want to win every match. The coach and his team — we need to be really focused on the process, what we have to apply day by day.

“The vision, the action on the court, technically, tactically, physically, mentally — also managing the schedule of tournaments, rest, the practice.”

Elevating careers through holistic guidance

In 2012, Tennis Canada enlisted Fontang to revive Vasek Pospisil, then stuck at World No. 140 with a game hampered by inconsistency. During their four-year collaboration, he propelled the Canadian to a singles high of No. 25 and doubles No. 4, teaching him to deploy underspin lobs in defensive stands and unleash down-the-line backhands to seize control in extended exchanges. Pospisil’s rise showcased Fontang’s knack for balancing physical prep with tactical shifts, ensuring recovery between events kept the energy high for net-rushing volleys on indoor surfaces.

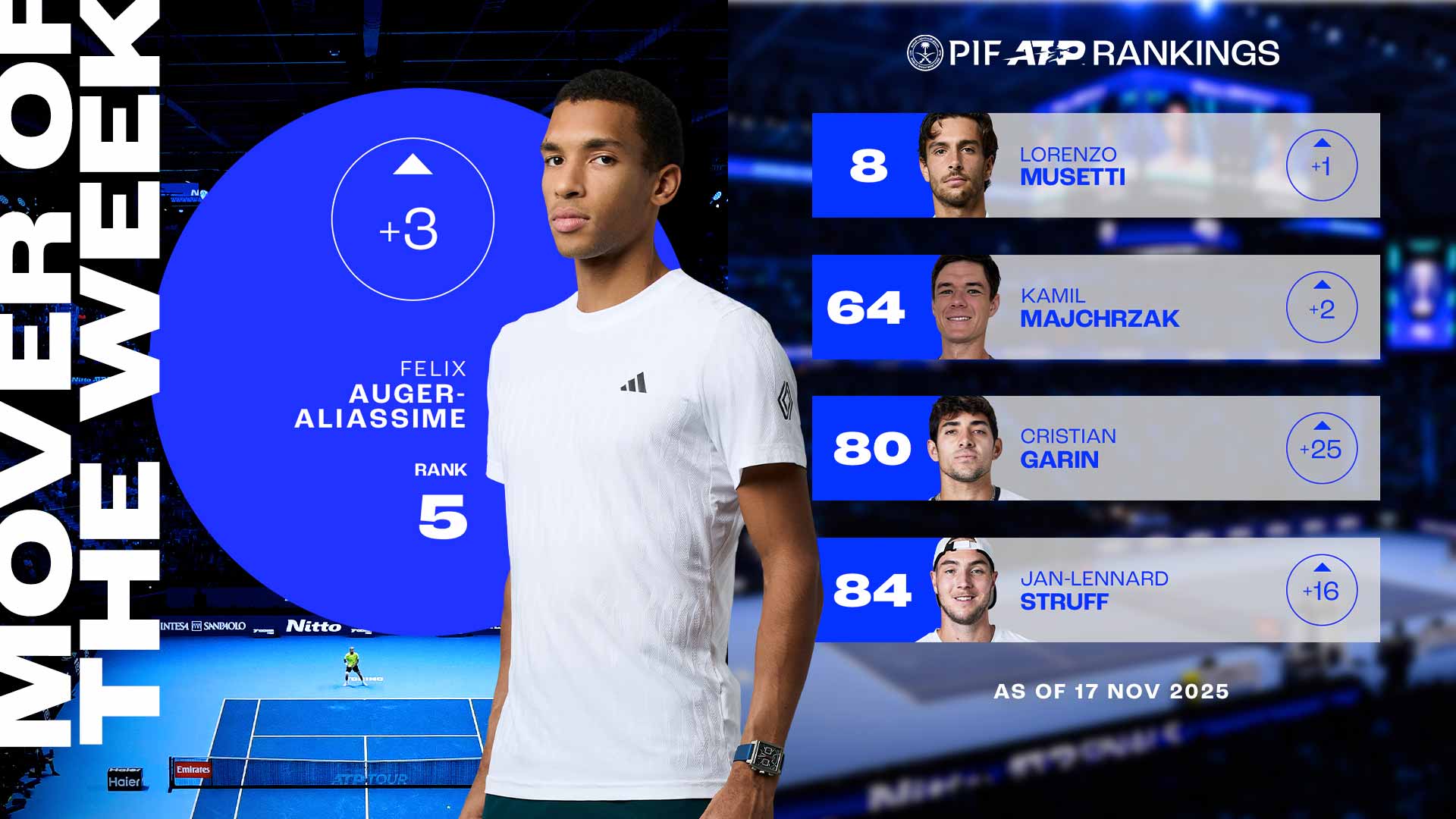

His current charge, Felix Auger-Aliassime, joined the fold at 16, with Fontang serving as co-coach alongside Guillaume Marx for the first two years before taking solo command in 2017. Together, they’ve scaled to No. 6, claiming seven titles including two in 2025 at Adelaide and Montpellier, by honing explosive serves that set up short-ball attacks against baseline grinders. Auger-Aliassime’s journey reflects the mental fortitude Fontang builds, turning mid-season slumps into late-year surges where crowd anticipation fuels precise inside-out patterns on fast hard courts.

At the core of this work lies a generalist philosophy, where Fontang oversees fitness, nutrition, and mental strategies while delegating to specialists. He stresses constant education for both coach and player, managing the entourage to align everyone with a unified vision that sustains performance through the tour’s nomadic demands. This orchestration prevents burnout, allowing charges like Auger-Aliassime to maintain focus during grass-court transitions or clay’s slow grinds, where a well-timed crosscourt angle can break an opponent’s rhythm.

“I believe you need to be a good generalist in a lot of fields, and you can choose the expert you need in those specific fields,” said Fontang. “I like the approach to educate your player and that means you have to educate yourself all the time to improve every day and to be a good generalist as a coach.

“For example, in fitness — at this level everybody has their own fitness coach — but you need to have a notion of fitness, of mental, of nutrition. Nowadays the role of the coach is also a manager because there’s a lot of people around the player. So you need to manage and to explain your vision well: Your vision as a coach for your player, that’s really important too.”

Lessons drawn from wide horizons

Born in Casablanca, Morocco, and a father of two, Fontang approaches coaching as lifelong learning, drawing from podcasts on politics and finance to enrich his tennis insights. He fondly remembers childhood viewings of Bjorn Borg and Mats Wilander, whose cool command on diverse surfaces inspires his own adaptations. Books by figures like NBA legend Phil Jackson provide transferable wisdom, such as using tempo control to disrupt aggressive returns or build momentum with down-the-line thrusts in deciding moments.

This broad curiosity equips him to navigate the psychological weight of the season’s end, where fatigue tests nerves as much as strokes. Fontang reveals that insights from team sports strengthen the player-coach bond, countering the isolation of individual competition. As Auger-Aliassime eyes year-end momentum, these layers position him to exploit indoor speeds, crafting victories that inch toward top-tier stability amid the rankings’ relentless churn.

“it’s a permanent process [of learning],” Fontang said. “To listen to some podcasts in different aspects; politics, geopolitics, finance, and directly from the sport from the physical aspect, mental aspect, nutrition. In all those fields you need to educate yourself because life is a non-stop improvement.”

“I like to read books because they give me inspiration. You can transfer a lot of things from other fields to my main field, which is coaching Felix,” said Fontang.

“I learned more from coaches from other sports because they are more like in the spotlight, and tennis was always less. In my time, we didn’t have much access to tennis coaches’ interviews, because it’s an individual sport and the players are in the front and the tennis coach is not in the front stage.“

Through it all, Fontang’s blueprint endures, preparing players to conquer not just opponents but the invisible strains of ambition, setting the stage for breakthroughs in the seasons ahead.