McEnroe’s Respect for the Relentless Drive of Tennis Icons

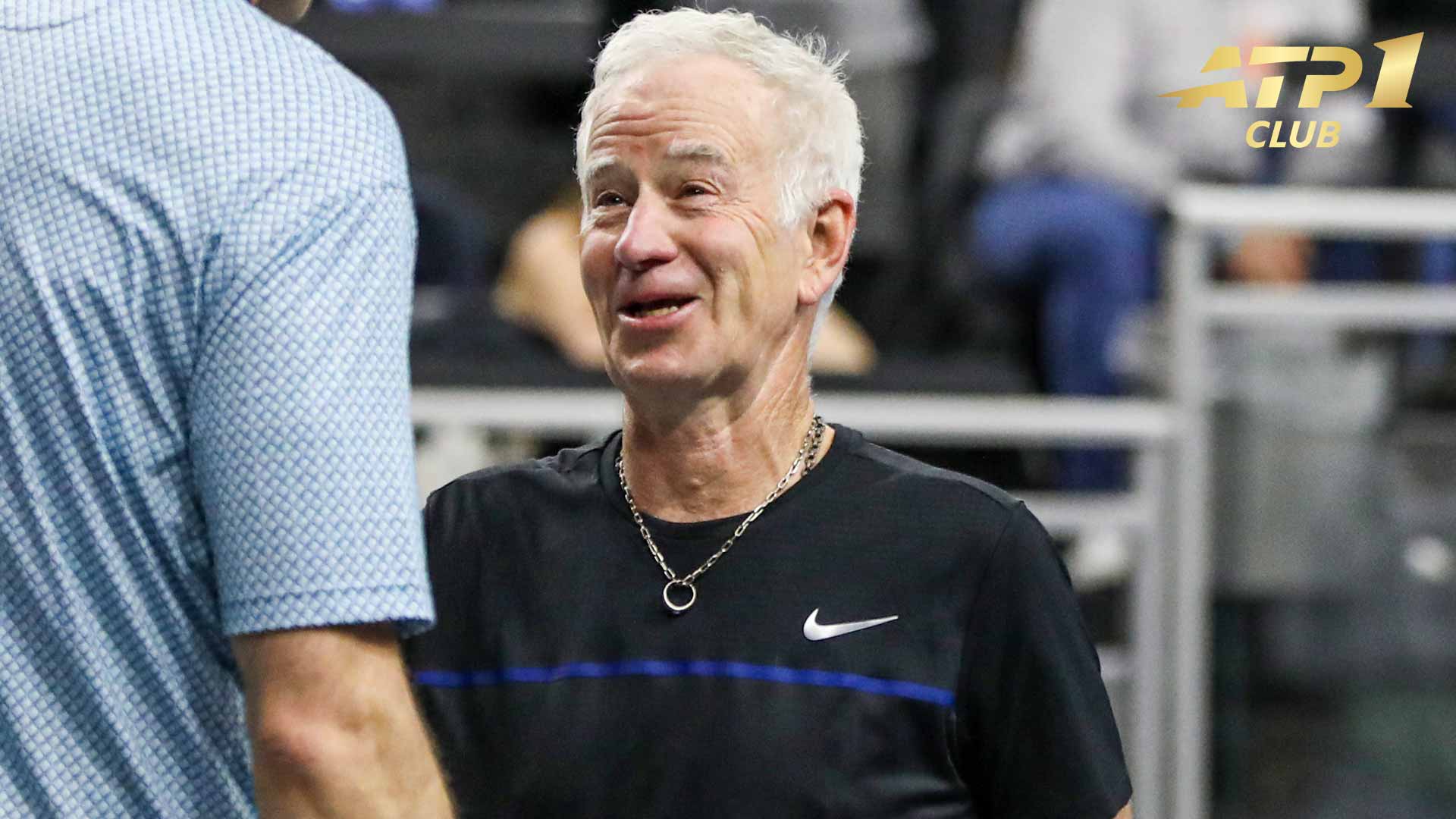

John McEnroe, courtside at the Dallas Open, shares the quality he truly admires in Djokovic, Nadal, Federer, and the new guard—a push that reshaped his view of the top spot.

John McEnroe settles into a chair at the Nexo Dallas Open, the sharp crack of aces echoing off the hard courts as players grind through early rounds. The American, who logged 170 weeks at No. 1 and four year-end finishes atop the rankings, now observes the pros with eyes honed by four decades away from the tour. What captures his admiration for Novak Djokovic, Rafael Nadal, Roger Federer, and the rising talents Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner is their ceaseless drive, a force that sustains dominance across grueling seasons on every surface.

This persistence stands out in the tactical battles McEnroe recalls from his era, where adapting to an opponent’s heavy topspin on clay meant countering with low slices or net rushes to disrupt rhythm. Djokovic’s sliding defense turns crosscourt rallies into endurance tests, much like Nadal’s high-bouncing forehands force errors in prolonged exchanges at Roland Garros. Federer’s fluid inside-out forehands carve through defenses on grass, setting a template for Alcaraz’s explosive one–two patterns that unsettle Sinner’s steady baseline game.

“They keep pushing. It might be a little late but the lesson I learned is maybe I should have pushed a little harder then instead of waiting to see what would happen,” McEnroe said. “So you get life lessons as you’re dealing with all this stuff that, later on, probably makes you a better person in the end.”

First steps to the summit

McEnroe first reached No. 1 in March 1980, but the ascent felt tentative, a computer ranking amid fierce rivalries that demanded constant adjustments. From Memphis in February ‘80 to the US Open in September ‘81, a year and a half passed before he fully displaced Bjorn Borg, whose topspin-heavy game on all surfaces required McEnroe to refine his serve-volley approaches and deep returns. That period tested his resolve, with each tournament swing—from indoor hard courts to outdoor grass—exposing the mental gaps in chasing the top.

The pressure built in subtle ways: a five-setter’s fatigue carrying over to the next week’s hard-court event, or the need to reset after a hostile crowd’s jeers. McEnroe’s climb mirrored the psychological demands he now sees in the modern stars, where defending points across a 52-week calendar means evolving tactics mid-season, like shifting from down-the-line passes on fast surfaces to crosscourt lobs on slower ones.

Shadows of great rivals

When McEnroe finally claimed undisputed No. 1, it aligned with Borg’s exit from full-time play in 1981, turning triumph bittersweet and overwhelming. The Swede’s retirement left a void that amplified expectations, forcing McEnroe to navigate the isolation of the summit without his fiercest foil. He adapted by deepening his returns to anticipate inside-in shots, sustaining his edge through third and fourth year-end No. 1 finishes despite the emotional weight.

“The first time that I hit No. 1 on the computer was a different time than when I was the No. 1 and that there was no doubt about it,” McEnroe reflected. “There was probably a year and a half between that happening in Memphis in February of ’80 to September at the US Open of ’81 when I supplanted Bjorn at that time as No. 1.”

“When it did happen, it coincided unfortunately as it turned out with my greatest rival deciding not to play any more. So it was gut-wrenching in a way,” he added. “That led to me struggling with feeling a bit like I’d walked into something that was a little bit overwhelming. And it took me a while to figure it out. And then by the time I figured it out, I was still out there finishing No. 1 the third, fourth year. But then after that, lifting myself to that level I was like, ’Alright, now I’ve shown them’.”

His final weeks at No. 1 ended in September 1985, more than 40 years ago, yet he holds seventh place among 29 members of the ATP No. 1 Club. This longevity echoes in the Big Three’s reigns, where Djokovic‘s hard-court returns or Nadal‘s clay sieges demanded similar reinvention to avoid dips.

Pride in the pursuit

McEnroe cherishes the humility of the chase, drawing from talks with Borg about the fine line between No. 1 and No. 2. Being second felt far superior to lower ranks, a mindset that fueled his efforts across surfaces where others crumbled—quick volleys on grass or steady baselines on hard courts. He applies this to today’s players, admiring how Alcaraz transitions from defense to attack with inside-out winners, mirroring the adaptability that kept him competitive.

“I appreciated it then, but I also appreciated being No. 2 in the world. I had this conversation with Bjorn quite a bit,” McEnroe noted. “He was like, ‘Look, if you’re not No. 1, what the hell difference is it being No. 2 or 100?’ I go, ‘Well, [No.] 2 is a lot better than 100’. So it’s just sort of the way you look at it.”

“To me, there are a lot of people out there trying to do their thing. So if you gave it the best you can give and you were 5 in the world or you’re 50, whatever it is, the pride you have to take is that moreso than, ‘Okay I’m No. 1 and therefore I’ve got to act a certain way’,” he continued.

McEnroe said: “To me, ultimately, I think that being able to say that for a period of three, four years, that I was the best and then there were other years I was one of the two of three best, that feels better as you get older.” As the Dallas Open crowd buzzes with anticipation for upsets, his words remind that true legacy stems from that inner push, propelling the next generation toward their own unbreakable peaks.

.jpg)